Given the growing complexity of computer networks, during the 1970s network researchers proposed various reference models to facilitate the description of network protocols and services. Of these, the Open Systems Interconnection (OSI) model [Zimmermann80] was probably the most influential. It served as the basis for the standardization work performed within the ISO to develop global computer network standards. The reference model that we use in this book can be considered as a simplified version of the OSI reference model 1.

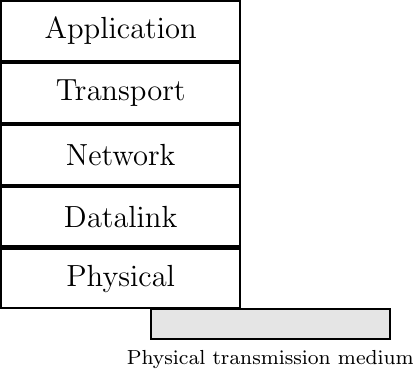

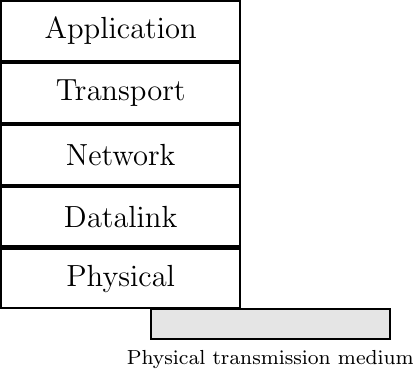

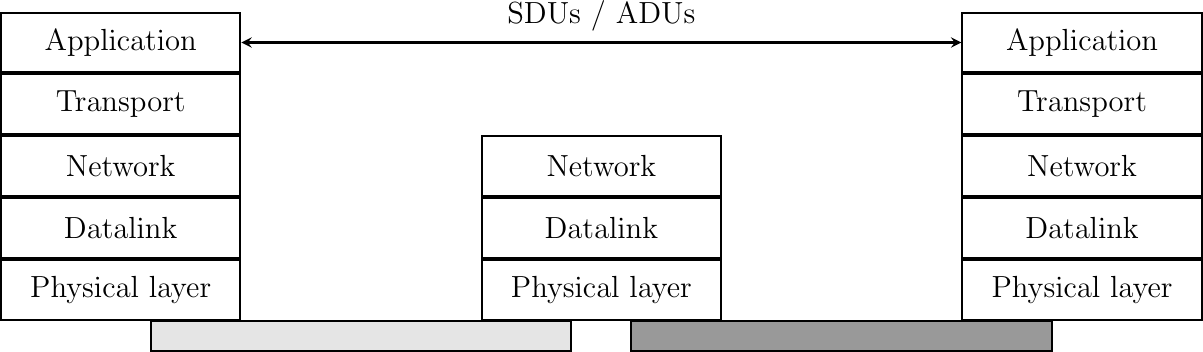

Our reference model is divided into five layers, as shown in the figure below.

The five layers of the reference model

Starting from the bottom, the first layer is the Physical layer. Two communicating devices are linked through a physical medium. This physical medium is used to transfer an electrical or optical signal between two directly connected devices.

An important point to note about the Physical layer is the service that it provides. This service is usually an unreliable service that allows the users of the Physical layer to exchange bits. The unit of information transfer in the Physical layer is the bit. The Physical layer service is unreliable because :

The Physical layer

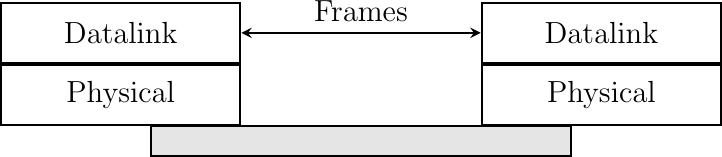

The Datalink layer builds on the service provided by the underlying physical layer. The Datalink layer allows two hosts that are directly connected through the physical layer to exchange information. The unit of information exchanged between two entities in the Datalink layer is a frame. A frame is a finite sequence of bits. Some Datalink layers use variable-length frames while others only use fixed-length frames. Some Datalink layers provide a connection-oriented service while others provide a connectionless service. Some Datalink layers provide reliable delivery while others do not guarantee the correct delivery of the information.

An important point to note about the Datalink layer is that although the figure below indicates that two entities of the Datalink layer exchange frames directly, in reality this is slightly different. When the Datalink layer entity on the left needs to transmit a frame, it issues as many Data.request primitives to the underlying physical layer as there are bits in the frame. The physical layer will then convert the sequence of bits in an electromagnetic or optical signal that will be sent over the physical medium. The physical layer on the right hand side of the figure will decode the received signal, recover the bits and issue the corresponding Data.indication primitives to its Datalink layer entity. If there are no transmission errors, this entity will receive the frame sent earlier.

The Datalink layer

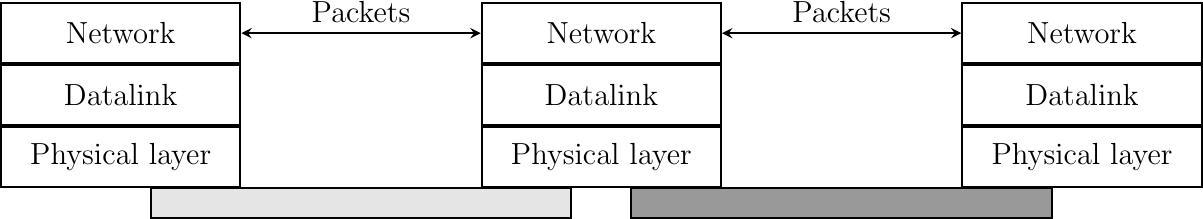

The Datalink layer allows directly connected hosts to exchange information, but it is often necessary to exchange information between hosts that are not attached to the same physical medium. This is the task of the network layer . The network layer is built above the datalink layer . Network layer entities exchange packets . A packet is a finite sequence of bytes that is transported by the datalink layer inside one or more frames. A packet usually contains information about its origin and its destination, and usually passes through several intermediate devices called routers on its way from its origin to its destination.

The network layer

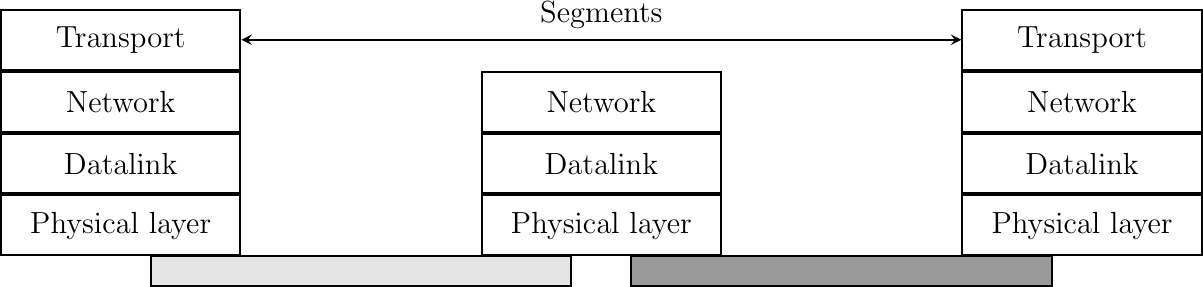

The network layer enables hosts to reach each others. However, different communication flows can take place between the same hosts. These communication flows might have different needs (some require reliable delivery, other not) and need to be distinguished. Ensuring an identification of a communication flow between two given hosts is the task of the transport layer . Transport layer entities exchange segments . A segment is a finite sequence of bytes that are transported inside one or more packets. A transport layer entity issues segments (or sometimes part of segments) as Data.request to the underlying network layer entity.

There are different types of transport layers. The most widely used transport layers on the Internet are TCP , that provides a reliable connection-oriented bytestream transport service, and UDP , that provides an unreliable connection-less transport service.

The transport layer

The upper layer of our architecture is the Application layer . This layer includes all the mechanisms and data structures that are necessary for the applications. We will use Application Data Unit (ADU) or the generic Service Data Unit (SDU) term to indicate the data exchanged between two entities of the Application layer.

The Application layer

In the remaining chapters of this text, we will often refer to the information exchanged between entities located in different layers. To avoid any confusion, we will stick to the terminology defined earlier, i.e. :

Two reference models have been successful in the networking community : the OSI reference model and the TCP/IP reference model. We discuss them briefly in this section.

In contrast with OSI, the TCP/IP community did not spend a lot of effort defining a detailed reference model; in fact, the goals of the Internet architecture were only documented after TCP/IP had been deployed [Clark88] . RFC 1122, which defines the requirements for Internet hosts, mentions four different layers. Starting from the top, these are :

Besides this difference in the lower layers, the TCP/IP reference model is very close to the five layers that we use throughout this document.

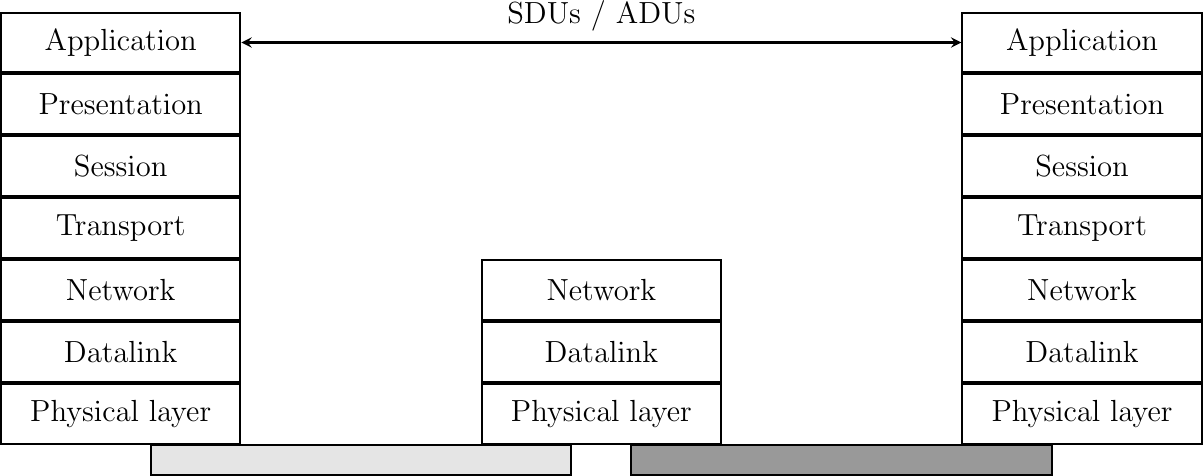

Compared to the five layers reference model explained above, the OSI reference model defined in [X200] is divided in seven layers. The four lower layers are similar to the four lower layers described above. The OSI reference model refined the application layer by dividing it in three layers :

The seven layers of the OSI reference model

An interesting historical discussion of the OSI-TCP/IP debate may be found in [Russel06]

There is now a rough consensus for the greater use of the Unicode character format. Unicode can represent more than 100,000 different characters from the known written languages on Earth. Maybe one day, all computers will only use Unicode to represent all their stored characters and Unicode could become the standard format to exchange characters, but we are not yet at this stage today.