Chapter 1 “A Fable for Tomorrow” seems like a curious title for the first chapter of a groundbreaking book steeped in science, based on meticulous research, and validated by experts of the day. Yet, Rachel Carson chose to present the public with an inventory of hazardous reports linked to chemical pesticides by beginning with a storybook format. Without mentioning a single pesticide by name, the author described a town that had experienced tragic incidents involving birds, bees, fish, domestic animals and people.

Concerning birds Carson wrote: “On the mornings that had once throbbed with the dawn chorus of robins catbirds, doves, jays, wrens, and scores of other bird voices there was now no sound; only silence…”

With respect to people she wrote about the children “who would be stricken suddenly while at play and die within hours.”

First time readers, believing the myth that Silent Spring is only about DDT may erroneously assume that the hazardous examples appearing in Chapter 1, including, a spring without birds and children dying suddenly pertain to the insecticide DDT – they would be wrong on two counts. First, Silent Spring considers a number of pesticides in addition to DDT (as is evident in many chapters throughout the book). Second, the report of children dying refers to a tragic incident involving the insecticide parathion from an entirely different chemical class than DDT, as described in Chapter 3.

Carson closed Chapter 1 by confirming that “This town does not actually exist, but it might easily have a thousand counterparts in America or elsewhere in the world.” She further asserted that the “Fable” is based on reliable evidence, [and] “every one of these disasters has actually happened somewhere and many real communities have already suffered a substantial number of them.” She added finally “This book is an attempt to explain what has already silenced the [bird] voices of spring in countless towns in America.”

Chapter 2 “The Obligation to Endure”

Rachel Carson began Silent Spring’s second chapter by establishing that life on earth had evolved gradually over centuries of constant adjustment between each species and the surrounding environment and that all life is interconnected. Widespread environmental contamination with the (then new) chemical pesticides over a relatively few years had not allowed for gradual adjustments of the non-target life forms that had been unavoidably exposed to these toxic hazards.

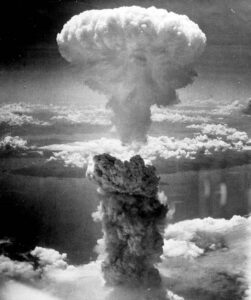

Author Carson compared the threats from these synthetic chemical pesticide contaminants released into the environment to the dangers associated with nuclear weapons, a topic very much in the public’s mind during the 1950s and `60s due to the Cold War and Cuban Missile Crisis. Sadly, in 2022, the nuclear threat issue has re-emerged mainly due to invasion of the Ukraine by President Putin’s Russia, a nuclear power. And sadly also, we are still confronting the adverse effects of synthetic pesticides, although generally not from the same chemicals as were present in Carson’s day.

Sixty years ago, Carson brought up conditions existing at the time (many of which occur today) that favor the continuation of pest problems and amplify the need to control them. For plants this includes the growing of monocultures in large simplified, unnatural environments, whether elm trees on city streets or fields of a single crop planted fence row to fence row. For humans there are the stressful situations accompanying war, poverty and disease as well as other conditions contributing to unhealthy lifestyles. Among the conditions contributing to pest problems, Carson included invasions by insect species that prey on plants, to areas previously isolated from these pests. Thus, the plants lack effective regional coping mechanisms unlike those that had evolved over time to deal with the invaders in their original home territory. She observed, “our most troublesome insects are introduced species.”

European Gypsy Moth, Pinned specimen of adult European/North American female (top) and male (bottom); USDA, APHIS, Plant Protection and Quarantine Archives

Rachel Carson noted that the release of DDT for civilian use after World War ll (WWll) was followed by the development of ever more toxic chemical pesticides. In Chapter 2, however, she did not mention any other chemical pesticide by name.

She advised that solutions to pest problems must come not from hazardous chemicals but instead from those trained in ecology with “the basic knowledge of animal populations and their surroundings”

This chapter concludes with Carson’s support for two basic human rights which remain universally relevant today. There is the right of citizens “to be secure against lethal poisons…distributed by private individuals or by public officials.” There is the “right to know” that is “to be in full possession of the facts.” Here Carson referred to the damaging risks that the insect controllers calculate for a chemical insecticide application. In 2022, moreover, the public’s right to know true facts is germane to all aspects of society from personal to community to national and even to international issues.

Chapter 3 “Elixirs of Death”

Elixirs” is a term usually associated with liquids having positive, life-affirming benefits; here it is coupled with death. Why? This mismatch draws attention to the benefits of the then popular synthetic pesticides that were being widely promoted by chemical manufacturers as well as to the serious adverse impacts of certain pesticides linked to fatalities of non-target species, including humans. At that time (in 1962) the general public remained largely unaware of the dangers posed to animals and even humans from exposure to pesticides such as: Chlordane, Dieldrin, Endrin, Parathion and Pentachlorophenol. 1 The adverse effects of these agents, when uncovered by researchers were reported mostly in scientific publications and rarely if ever communicated to the public by the popular press, or listed on pesticide product labels. In Silent Spring’s third chapter, author Carson identified for the first time active ingredients (including the five mentioned above) found in pesticide products and linked to serious adverse effects on domestic animals, fish, bees, children, workers and others.

In addition, Carson provided a toxic profile of arsenic (a natural element), that had been widely used in pesticide products to kill insects and weeds for a number of years prior to 1945 – and was still being used in 1962. 2

In Chapter 3, Rachel Carson focused primarily on the adverse impacts of insecticides from two specific chemical classes the chlorinated hydrocarbons (aka organochlorines), and the organophosphates (OPs). Pesticides from both chemical groups were widely popular when Silent Spring was published and the public was generally unaware of the potential for serious harm following exposure to them. Finally, Carson briefly introduced toxic chemical herbicides that had been linked to fatalities in humans as well as to cancer.

Chlorinated hydrocarbons have been among the most persistent insecticides – that is – they could be present for years, following release into the environment. These long-lived chemicals were found to act primarily on an animal’s nervous system, but could adversely impact other animal organs. They were described as broad spectrum poisons that do not distinguish between bad bugs and good bugs. Their adverse impacts could include long term hazards such as cancer, as well.

Carson explained the reputation for safety of DDT (dichloro-diphenyl-trichloro-ethane, a chlorinated hydrocarbon) in part following its use during WW ll as a powder in combating lice, because in the powder form the chemical is not readily absorbed through the skin. She reported, however, that by 1950 FDA scientists had concluded that likely the potential hazard of DDT had been underestimated.

DDD Concentrations in the Clear Lake Food Chain.

Of particular note, DDT was found to be passed up the food chain due to its solubility in fat and its long term storage in animal tissues with a high fat content. When Silent Spring was published, FDA had forbidden the presence of insecticide residues in milk shipped interstate. 3

Carson focused on several specific chlorinated hydrocarbon insecticides linked to human and animal deaths that were from the cyclodiene group. 4 They included:

Dieldrin (a chlorinated hydrocarbon – a cyclodiene chemical) was found to be absorbed through skin when in solution. Carson reported that several spray applicators had died suddenly when Dieldrin was substituted for DDT.

Endrin (a chlorinated hydrocarbon – a cyclodiene chemical) was linked to deaths of fish and cattle. Carson described an example of a year old child whose floor had been sprayed with Endrin for roaches. Subsequently, the family’s pet dog died, and the baby suffered permanent brain damage.

Chlordane (a chlorinated hydrocarbon similar in structure to Dieldrin) was in the opinion of the US Food and Drug Administration’s Dr. Lehman: “one of the most toxic insecticides – anyone handling it could be poisoned.” Carson reported an incident in which the victim accidentally spilled a 25% solution of Chlordane on his skin and developed symptoms of poisoning within 40 minutes; he died before help could be obtained.

Organophosphates (OPs), from another class of broad spectrum chemical insecticides were found to be much less persistent but generally of greater immediate toxic potential than the chlorinated hydrocarbons. OPs were widely available in Rachel Carson’s day. Some OPs are still registered by the US Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA) in 2022. OPs act on the nervous system of animals at different sites than those impacted by the chlorinated hydrocarbons. OPs can break down to harmless chemicals within weeks after application whereas the chlorinated hydrocarbons may persist for years. OPs were and are, however, considered to be generally of more immediate toxicity for humans, birds, fish and bees than the chlorinated hydrocarbons.

Rachel Carson noted that repeated exposures to OPs may increase an individual’s sensitivity to the toxic potential of an organophosphate insecticide, until ultimately he or she reaches the threshold of acute poisoning and then may be pushed over the brink by exposure to a very small additional amount of the same (or another) OP. Parathion was an organophosphate insecticide popular in the decades between 1945 and 1962.

For Parathion, Carson cited the example in which, “…two children found an empty bag and used it to repair a swing. Shortly thereafter both of them died and three of their playmates became ill. The bag had once contained parathion…tests established death by parathion poisoning.” (page 28, Silent Spring )[underlining added]

Parathion was reported as fatal to honeybees, and at one time was a favored instrument of suicide in Finland.

The chemical herbicides, a different group of pesticides, Silent Spring’s author warned, also had been linked to fatalities: “The herbicides, then, like the insecticides, include some very dangerous chemicals, and their careless use in the belief that they are “safe” can have disastrous results.” (page 35, Silent Spring)

For the herbicide Pentachlorophenol, Carson included a tragic report that had been documented by the California Dept of Health. A tank truck driver was mixing pentachlorophenol with diesel oil for a cotton application. “As he was drawing the concentrated chemical out of a drum, the spigot accidentally toppled back. He reached with his bare hands to regain the spigot. Although he washed immediately, he became acutely ill and died the next day.” (page 36, Silent Spring)

Systemic insecticides a category of chemical pesticides with distinctive actions in plants was introduced by Carson in Chapter 3. This group included OPs with the ability to permeate all tissues of a plant and make them toxic to insects feeding on them. Systemics can be taken up through plant roots or by way of the seeds. When systemic insecticides are applied to seeds prior to planting; “they extend their effects into the following plant generation and produce seedlings poisonous to aphids and other sucking insects.” (p. 33, Silent Spring)

The discussion of Chapter 3, gives an indication of the toxic range and scope of the chemical pesticides that Carson covered in Silent Spring – obviously more than just DDT.

By reporting on the deaths linked to pesticide exposure of animals and humans, Carson drew attention to the interrelatedness of all life and (in the words of Frank Graham, Jr.) she showed “the depth of her sympathy for all living things.” (Always, Rachel, “Introduction”)

Below Are Questions Related to the April 2022 Discussion of Silent Spring Chapters 1, 2 & 3

(Note: Read Rachel Carson’s text for a perfect score)

Which, if any pesticides did Carson mention in Chapter 1 “A Fable for Tomorrow?”

What were the two “rights” that Rachel Carson mentioned in Chapter 2 “The Obligation to Endure?”

In Chapter 3, “Elixirs of Death,” what insecticide was responsible for the tragic event involving children who would be “stricken suddenly while at play and die within a few hours?” Where did the incident occur?

In Chapter 3, Carson presented information about the systemic insecticides. What are their actions in plants?

What character from Greek mythology was used by Carson to introduce the systemic insecticide concept?

Footnotes

1. As of 2022 all of the 5 chemical pesticides mentioned here have been banned or cancelled for most applications by the USEPA (founded in 1970) as well as other pest control chemicals that became available after 1945 – the end of World War ll.

2. By today many different forms of arsenic in pesticide products have since been cancelled, a few, however, continue to be available.

3. From today’s perspective, looking back at the U.S. federal regulatory climate existing in the 50s and 60s, it is questionable that such protections could have effectively taken place.

4. Cyclodienes are a chemical subgroup of the chlorinated hydrocarbons. They were known to be well absorbed through the skin and generally found more hazardous than DDT.